The Graceful Chase for One’s Dream

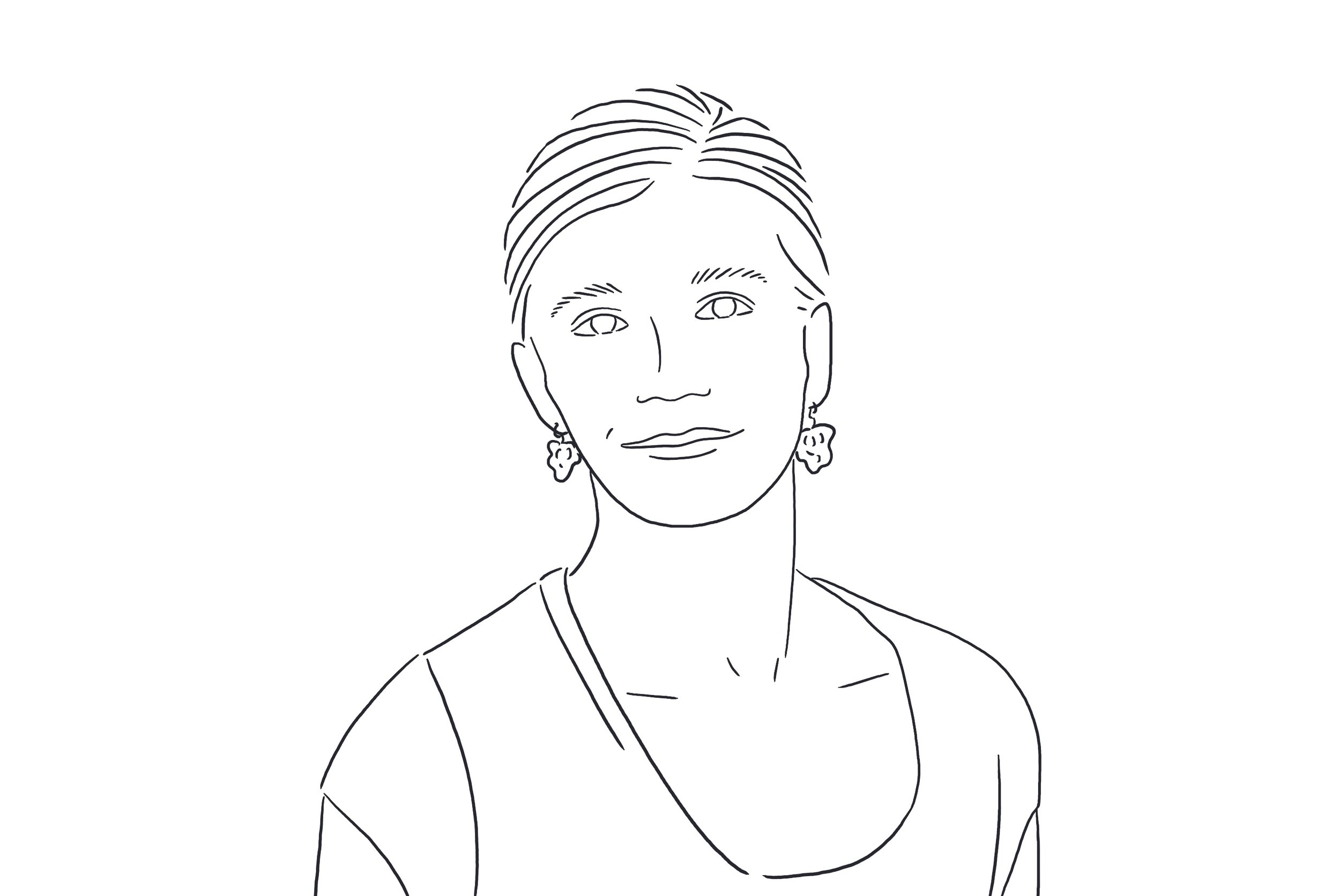

In Conversation with Natasha Illum Berg.

Natasha is a professional hunter, author, and conservationist from Sweden and Denmark, living in Tanzania. The only female professional hunter in East Africa, Natasha has studied humans in the open field and forged her opinions – one chase at a time. In her own words, she puts her trust in nature as a hunter and questions and explores humans as a writer, both with insatiable curiosity. Natasha’s journey and poetry are presented in six books translated into nine languages. Recently, three of them were made available as audiobooks in English. She is a proud tribe member of “people who read a lot, grow things, and have an opinion.”

Tusker Club – What sparked your love for nature, and how did this passion evolve into becoming your career today?

Natasha Illum Berg – I grew up on a farm in Sweden. My grandfather was a leading conservationist who contributed to saving five species. I have always felt very safe in nature, which isn’t always true with humans. If I ever got scared as a kid, I would run into the forest where I felt no one could harm me.

Humans are more unpredictable than nature, and they can hate. When animals attack, it is never out of hate. In my opinion, the fear of death distinguishes humans from the rest of the animal kingdom. The anticipation of death may explain why many of us are afraid of living when we live and afraid of dying on our deathbed.

TC – You have written several books, and some are quite personal. How do you create space for authenticity and vulnerability in your writing process, particularly within an environment often associated with strength and emotional restraint?

NIB – I am always vulnerable! Confusing being hard with being tough is a common mistake. I am like a reed: tough, but never hard. My emotions are always available.

Hard people may aim for toughness, but they don’t help anyone, not even themselves. This inclination may come from the belief that life shapes us or even scars us, or it could result from the pressure of navigating a life that is not always within our control. Priding oneself on being battle-hardened may be rooted in a feeling of insecurity and a tendency to suppress emotions.

On the contrary, people who are kind recognise that the most important thing is to choose who we want to be. Hence, it requires establishing boundaries that allow for self-compassion and acceptance of others.

Confusing being hard with being tough is a common mistake.

TC – How do toughness and kindness play into your approach to performance?

NIB – As a writer, I honour language and make sure that it doesn’t fail me. With experience, I prefer the notion of achievement over performance. At some point in life, you truly know that you are doing your best, that you are being appreciated by people you respect, and that you have experience. It is important to build a name for oneself, but achievement brings confidence and allows for kindness.

This is something I experience as a hunter as well. There is a rhythm to hunting. Going on a chase is like following a certain song. Whether it starts high or low, the tune will change. Sometimes, animals will get away; sometimes, we follow the wrong track or must let the animal get away because it is too young, for instance.

In my 30 years in the hunting world, I have learnt to listen to the song of the bush. Hunting is not about shooting an animal, it is about experiencing a nearness to nature, coming home to the story that goes with the chase, and grounding our identity in that reconnection with wilderness.

I prefer the notion of achievement over performance.

TC – In your approach to hunting, how do you define fairness?

NIB – Fairness has to do with being clear about what we are doing and why. Hunting safaris in Tanzania are typically attended by seasoned clients. Only a handful of them are active in the hunting reserve at a given time. And they pay a lot of money to get access. As such, hunting releases the pressure on ecosystems and contributes to wildlife conservation over large areas.

Fairness also has a lot to do with the process. The art of hunting is not about shooting. It is about getting close to the animal. We hunt on foot and crawl to approach it. Our practice is no different to what other animals do. Stalking close makes you feel empathy toward the animal, responsibility toward your actions, and stewardship toward your environment. It lets you be aware of your ego and fear.

Distance takes away responsibility. The trap for a good long-distance shot is losing the connection to nature, eventually leading to the loss of oneself.

TC – You lead a life many would consider strenuous. How do you manage your energy while on the chase?

NIB – While hunting, we follow the rhythm of nature. We start early. Rest in the comforting shadow of a tree during the hot hours. Refresh our numb feet in a stream.

As days pass, I push my clients beyond their comfort zone. Letting go of control and easing into their environment helps release energy.

After three weeks in the bush, I go home to my daughter and take on my role as a mother, checking in with her. This is facilitated by a ritual which consists of bringing back the heart of an animal we hunted and cooking it in a stew, telling the story of how it was tracked.

And then I sleep for 16 hours straight… And I am ready to go out again.

TC – Following one’s dream and overcoming fear are common invitations. What practical advice would you give leaders to make it happen?

NIB – Having a dream is the biggest gift there is. It is a point on the horizon that lets you know where you are. It also requires acceptance of the hardships that come with the journey. Chasing a dream is hard. Hence, when it doesn’t work, start again. And if it still doesn’t work… start again. Feel the pain and don’t give up, because having a guiding light is a grace that protects us from feeling lost.

Fear is the opposite. We pin it down, accept it, and move into it, but we also must find an antidote. My fear is time passing. Therefore, I try to spend mine well, as if I were putting an elastic band on it. Not wasting time lengthens it.

This is also why, when it comes to work, I like to be addressed as an individual, not through a gender lens. There are differences between women and men. But I want people to focus on what drives me as a person, my fears, and my dreams.

I want people to focus on what drives me as a person, my fears, and my dreams.

Interview by Baptiste Raymond, 01/2024.